Posts Tagged ‘Art’

Four-letter words like Love and Hope

Four-letter words like Love and Hope

Sometimes a song comes along with a shitty, repetitive chorus, and it all goes down like melba toast…like when John Mayer once encouraged us to “Say what (we) mean to say” in eight not-so-different ways. Other times, there’s the repetitive chorus that we’re meant to be able to remember—even while shit-faced on Patron…like when Taio Cruz tells that “Little Bad Girl” to just “Go” already, stamping along in time to some David Guetta beats.

Sometimes a song comes along with a shitty, repetitive chorus, and it all goes down like melba toast…like when John Mayer once encouraged us to “Say what (we) mean to say” in eight not-so-different ways. Other times, there’s the repetitive chorus that we’re meant to be able to remember—even while shit-faced on Patron…like when Taio Cruz tells that “Little Bad Girl” to just “Go” already, stamping along in time to some David Guetta beats.

But once in a while the simplest, most repetitive phrase in a song can mean everything. This is when you’re breathing that rare air of The Doors’ “Indian Summer.” Jim Morrison and Robby Krieger work their magic(k), and suddenly, “I love you the best. Better than all the rest” is like the most profound lyric you’ve ever heard. Sometimes a pop song comes along and hits in just the right way, at just the right time. Such is the case with Rihanna’s new song, “We Found Love.”

“We found love in a hopeless place.” There it is: the moment. You don’t need to say anything else. There’s no need to riff on an explanation of that; you’ve probably known what it means since the beginning of time. “We found love in a hopeless place.” That’s everything. You know exactly what it is.

Hearing this song while thrift store shopping for used clothes that the character in my new play might wear does things to me. Powerful things. It’s like a huge homage to a time in my life when I did have hope, and I don’t just mean a general kind of universal hope for the future, the suspension of doom that was the 1990’s, I mean on a personal level. It’s those opening synth sounds that remind you of Crystal Waters’ “Gypsy Woman”…it’s like you already know this song, could recognize it anywhere, always knew it. When you listen to what Calvin Harris did, the reference to 90’s house music right from the very first moments of the track, already you’re transported to a time when people weren’t glued to their cell phones or email, when there was this new kind of strangely innocent thing, this dance music, this acid house, this scene that had its grisly dark side of OD’s on the dancefloor, but more than that just had a lot of love. This is the synthesized voice of love in analog.

And then there’s the video. This is no Lady Gaga over-priced hack-job imitation of the material girl’s ambitiously blond anthology, in which Gaga, the born-rich “artiste,” stares gauntly into the camera in an attempt to convince you that there’s something big and emotional and powerful in her when in fact it’s just another shade of neon in her vacancy sign.

No!

The beauty from Barbados actually feels things in this video and we feel them too. The people who put this video together knew what the hell they were doing. They stole all the right stuff: the dilating pupils and bathtub moments from Requiem for a Dream, the grey-skied open fields and flop houses from Trainspotting…this is divine 90’s montage: this video is perfect. It’s perfect because it’s actually presenting images from an era that was hopeful, in the same way that Harris’ musical track calls on the sounds of some seemingly-ancient rave time, so you feel the hopelessness of now even more. Sure, they could have shown images of children playing joyfully by fracking wells, or couples embracing while on the unemployment line in, like, Gary, Indiana or something. That would have been love in a hopeless place too, but that would have been too explicit. All that is already implied. And it doesn’t matter that there are shades of Rihanna and Chris Brown’s relationship in the video. Nobody cares. Chris Brown is just fuel for the story. And the story is beautiful. This past weekend, a poet friend of mine asked me if I’ve ever really been in love. I think you know love when you see it and the real thing looks just like this music video and sounds just like this song. I might as well just say it: I wish I could afford to do something this good…and I can’t.

Instead, I spend time at Zuccotti Park and sometimes I sing down there with just the voice that I have, a voice that can almost sort of compete with the sound of jack-hammers and the general assembly. And it is beautiful. It is one of the only beautiful things I’ve experienced for myself as a performer in a long time. It is beautiful, but it is small. Too small for me. I always long to do something meaningful. I’m not always that hopeful about it. For now, I’m just one RSS feed in a giant trough of RSS feed. So I become a part of something, something that I’m already a part of: the 99 percent. I’m no Rihanna. I wish I could be Rihanna. I wish this were my song, but I’m faceless and nameless and the best my voice can hope for is to be a part of the roar of the great din, the crashing on the shore, which has its own cacophonous majesty. In a sea of stars, there’s no shine in particular, just sameness. But it’s an amazing kind of sameness. Invisibility is a kind of superhero power too. This coming moment might be the end of the era of having a name. In so many Guy Fawkes masks, we’re all Anonymous and who knows what kind of songs will come from the nameless, but maybe we will find a more hopeful place.

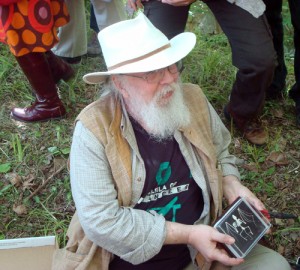

Thanks to Michael Geffner for the photo at OWS Poetry Assembly, above.

Entering the Temporary Art Zone with Hakim Bey

Entering the Temporary Art Zone with Hakim Bey

“The art, such as it is, comes into existence only in the moment of its own disappearance; afterwards it will be invisible—except to the spirits” – Peter Lamborn Wilson

• • •

On May 15th 2010, Peter Lamborn Wilson, known to many as Hakim Bey, completed another happening in a series of events aimed at re-enchanting the landscape of forgotten or not-yet-revealed sacred places in upstate New York. These acts of “Endarkenment,” a term Peter uses to mean “fear & respect as well as love for Nature,” are the culmination of his last ten years of research in Ulster County and the surrounding areas. He’s putting the magick he dug up back into the land.

On May 15th 2010, Peter Lamborn Wilson, known to many as Hakim Bey, completed another happening in a series of events aimed at re-enchanting the landscape of forgotten or not-yet-revealed sacred places in upstate New York. These acts of “Endarkenment,” a term Peter uses to mean “fear & respect as well as love for Nature,” are the culmination of his last ten years of research in Ulster County and the surrounding areas. He’s putting the magick he dug up back into the land.

Peter has called this a “temporary landscape installation piece.” It is art that disappears and defies a fetishized place on the  gallery wall. While it bears a resemblance to landscape art, it is more than that, for its goal is to enact the magick of enchantment on the land where each work is performed. The documentation of each of these works includes a hand-written essay, and this May 15th working also featured a large storyboard with pictures and photographs significant to the occasion.

gallery wall. While it bears a resemblance to landscape art, it is more than that, for its goal is to enact the magick of enchantment on the land where each work is performed. The documentation of each of these works includes a hand-written essay, and this May 15th working also featured a large storyboard with pictures and photographs significant to the occasion.

After Peter’s short talk about his research leading up to this event, a few helpers went ahead to make preparations, followed by Peter and his large box labeled “Jukes.” Slowly, the rest of us followed in single file along the narrow towpath where mules used to tread, hauling boats, when the Delaware and Hudson Canal was operational.

In my understanding of it, there were three main groups called forth for reawakening in this work:

one group that has already disappeared, one that is disappearing, and one that now returns.

The group that has already disappeared is known as the Jukes, or at least that’s the name that flawed social scientists gave to this now infamous community of families when they were the target of eugenics studies in the 1800’s. The flaws in these studies have since been recognized, but what still remains fascinating about the Jukes is the reason that they were targeted for such studies to begin with: they were what Peter calls, “a drop-out society,” not unlike the modern day Ramapough Mountain Indians from New Jersey, who were the subject of the recent New Yorker article “Strangers on the Mountain.” But the Ramapough Mountain Indians,  or “Jackson Whites,” as they have been called, have kept their society, even with the skyscrapers of New York threatening on the horizon. They have also kept their mountain – even with the enduring effects of the toxic waste that the old Ford factory dumped on it decades before. The Jukes have not been so lucky – if you can call it luck. While descendants of the Jukes surely still exist, their isolated drop-out community has vanished, and they seem a distant legend in the Ulster County of 2010. All that remains of the Jukes today can be found in a poorhouse graveyard in New Paltz that was re-discovered in 2001, and in the records kept by the poorhouse and those in the archives of the SUNY Albany library. The once vibrant living community of Jukes has now vanished.

or “Jackson Whites,” as they have been called, have kept their society, even with the skyscrapers of New York threatening on the horizon. They have also kept their mountain – even with the enduring effects of the toxic waste that the old Ford factory dumped on it decades before. The Jukes have not been so lucky – if you can call it luck. While descendants of the Jukes surely still exist, their isolated drop-out community has vanished, and they seem a distant legend in the Ulster County of 2010. All that remains of the Jukes today can be found in a poorhouse graveyard in New Paltz that was re-discovered in 2001, and in the records kept by the poorhouse and those in the archives of the SUNY Albany library. The once vibrant living community of Jukes has now vanished.

The second group, the group that is in the process of vanishing, is the bat community. All along the East Coast and into the Midwest, bats have been found dead in the hundreds of thousands.  The bats are dying of “white-nose syndrome,” so named for the white fungus, Geomyces destructans, that can be seen on the muzzles of infected bats. It is still uncertain whether the fungus is the disease or whether it is able to take hold of an immune system already weakened by some other disease, though it seems that the fungus itself is the culprit. Bats are a major predator to insects, not just the insects that interfere with us on a hot summer day, but also those that interfere with the growth of crops. The threat of imbalance in the ecosystem, as well as the possibility of extinction for many species of bats, is a serious concern for us all as we watch this community of animals suddenly disappear.

The bats are dying of “white-nose syndrome,” so named for the white fungus, Geomyces destructans, that can be seen on the muzzles of infected bats. It is still uncertain whether the fungus is the disease or whether it is able to take hold of an immune system already weakened by some other disease, though it seems that the fungus itself is the culprit. Bats are a major predator to insects, not just the insects that interfere with us on a hot summer day, but also those that interfere with the growth of crops. The threat of imbalance in the ecosystem, as well as the possibility of extinction for many species of bats, is a serious concern for us all as we watch this community of animals suddenly disappear.

The last group, the one that returns, is the cement itself, which was to be the bonding agent of all that went into this day’s working of Endarkenment. Standing on the aqueduct bridge abutment designed by Roebling in 1850 and overlooking the Rondout Creek, it seemed only fitting that the cement used for this occasion should be Rosendale Natural Cement, which was the business that founded the nearby town of Rosendale during the construction of the Delaware and Hudson Canal. The cement was first discovered in Rosendale during the excavation of the canal bed for the D & H Canal in 1825, and would later be used as one of the materials in the building of the canal itself. Rosendale Natural Cement was also used in the construction of Roebling’s aqueduct bridge, the remaining abutment on which we then stood, and in his later and more famous project, the Brooklyn Bridge. Despite the popularity of Rosendale Cement in the nineteenth century, the introduction of faster-setting Portland Cement meant the end of natural cement production in the twentieth century. By 1970, the last of the cement mines in Rosendale were closed. Natural cement was no longer available.

But in 2004, natural cement made a surprising return when Edison Coatings, Inc decided to resurrect production of Rosendale Natural Cement. The main reason behind this comeback was the need to restore buildings and monuments that were originally constructed using natural cement,  though it turns out that Rosendale Natural Cement is actually “greener” than modern Portland Cement. Due to its much lower firing temperatures and the ease of grinding, natural cement requires less energy to produce.

though it turns out that Rosendale Natural Cement is actually “greener” than modern Portland Cement. Due to its much lower firing temperatures and the ease of grinding, natural cement requires less energy to produce.

As we gathered around Peter to watch this artwork in its vanishing, an artwork that is being done for those who vanish, the scent of copal mixed with other incenses – those he had burning on the rock before us, and those of the forest itself.

The artwork happened simply. There was little ceremony, perhaps to the confusion of some in attendance who had hoped for a chant or a reading. Peter presented items, one by one, and placed them into a hole in the ground that would be filled with cement. Among these were crystals, a fancy bat skeleton from Carolina Biological, the remains of the incense itself…it made me wonder: must things be buried that they may return? Do we re-enchant our environment when we return to the point zero?

The artwork happened simply. There was little ceremony, perhaps to the confusion of some in attendance who had hoped for a chant or a reading. Peter presented items, one by one, and placed them into a hole in the ground that would be filled with cement. Among these were crystals, a fancy bat skeleton from Carolina Biological, the remains of the incense itself…it made me wonder: must things be buried that they may return? Do we re-enchant our environment when we return to the point zero?

For Peter’s magickal purposes in this act of art, I believe it was significant that the natural cement local to this area, the one element in the work that had gone from a state of disappearance into new life, should be the bonding agent for all the others. As the creation of this temporary installation piece was executed, we watched closely as items disappeared into the hole, as their physical passage from the box labeled “Jukes” into the hole before us disappeared into memory. All of this was then sealed by cement and rocks found around the site the day before. While the process of art may have vanished, the evidence of the act endures. Like the Brooklyn Bridge, the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, and Grand Central Terminal, this momentary work was made using Rosendale Natural Cement. Its purpose is beyond that of a monument, but the place of Endarkenment was built to last just the same, even if it was now only visible to the spirits, as Peter says.

After we traveled back along the narrow towpath and out of the woods, a little boy who was playing pointed up to the sky, and we all saw it: a small rainbow showing itself faintly through the trees, though it hadn’t rained at all. The enchantment was complete, and the signs of this were not only visible to the spirits, but also to us.

*** Peter’s statements that have been quoted here are from the press release of a previous related event. You can read his writing on that event here:

http://www.sevenpillarshouse.org/article/first_vanishing_art/

7VPZM2AUKGJM

Spargel, Fish, and Farewells

Spargel, Fish, and Farewells

by Ayesha Adamo

It seemed that the moment my plane landed in Berlin, Spargel season had officially begun. There was hardly a restaurant in the city that wasn’t offering some sort of Spargel-special, four courses of Spargel…even dessert. I had  never heard of Spargel before, but I learned pretty quick. Spargel is this thick white asparagus that Germans seem to go crazy for, especially because it’s only available for two weeks out of the entire year. It’s a little bit phallic looking, and maybe that’s part of the charm, too. You can see piles of it here, in this photo I took at the Turkish market in Kotti:

never heard of Spargel before, but I learned pretty quick. Spargel is this thick white asparagus that Germans seem to go crazy for, especially because it’s only available for two weeks out of the entire year. It’s a little bit phallic looking, and maybe that’s part of the charm, too. You can see piles of it here, in this photo I took at the Turkish market in Kotti:

The fantastic deli, “Rogacki,” where I got my first taste of Berlin, was no exception to the rule of Spargel either.

Rogacki is the deli to end all delis. I mean, I used to deeply mourn the loss of Second Avenue Deli down in the East Village after it lost the rent war to a Chase Bank branch (which I suppose is exactly what all those yuppies that have taken over the neighborhood deserve anyway), but Rogacki is in a whole other class.

Rogacki is in Charlottenburg on Wilmersdorfer Strasse, just half a block from the Bismarckstrasse U-bahn. Everyone stands at the counter to eat, though there were a few  tables out front in recognition of the spring weather.

tables out front in recognition of the spring weather.

In addition to the seemingly endless window cases of beautiful sausages and deli meats, this place has some serious fish  (the big guy with the sad look on his face at the top of this article is also a Rogacki resident). We ate the most amazing fish soup and grilled fish with vegetables, all prepared by the no-nonsense ladies at the counter before our eyes. In keeping with the reputation

(the big guy with the sad look on his face at the top of this article is also a Rogacki resident). We ate the most amazing fish soup and grilled fish with vegetables, all prepared by the no-nonsense ladies at the counter before our eyes. In keeping with the reputation  of this family-run business that started in 1928 selling fish exclusively, they still smoke their own fish and eel on site here. But nowadays, there’s also fresh turkey,

of this family-run business that started in 1928 selling fish exclusively, they still smoke their own fish and eel on site here. But nowadays, there’s also fresh turkey,  venison, duck and on and on…

venison, duck and on and on…

In general, Berlin is a great place for fish and seafood, and my last night’s dinner at the amazing Turkish-run Fisch Restaurant was the perfect bookend to my Rogacki experience.

Balikci Ergün is on Lüneburger Strasse under the S-Bahn, across the Spree and not so far from Bellevue Station. You will know it by the blue and yellow sign saying “Fisch Restaurant.”

I’m pretty sure that the entrance on Lüneburger Strasse is a back entrance devoted to their fish distribution business, but after a few moments of confusion and seeing what was behind door number one, two and three, I eventually found my way into the restaurant.

This last night was a night to say goodbye to Berlin, and to Maria Thereza Alves and Jimmie Durham, whose three exhibits during gallery weekend and talk at the House for World Culture with Mick Taussig were an important part of my visit.

The conversation at our table twisted and turned into and out of politics and Art, Europe and the Americas. For the struggling and flailing artist that I am, it was fascinating to hear about how someone with a career as enduring as Jimmie’s would repeatedly turn down the opportunity to have a PBS documentary done on his life and work, responding that this sort of documentary kills the artwork, and the artist who made it, every time. I guess it’s the reaction I would expect from the man who’s just displayed a gallery of modern-art-stuffed-mooseheads (like what you’d see in a fancy hunting lodge, except this was Art – not taxidermy). It’s hopeful to see someone cleverly poking fun at the bourgeois trophies that great works of Art have become – or always were, perhaps. But for a young creative who’s tired of trying to reinvent her Art’s PR campaign on a weekly basis, and who enters a state of nearly-epileptic joy anytime some stranger deigns to add a thumbs-up “like” to her latest facebook post, the idea of turning down a documentary makes the eyes a little moist…a little moist. I get it, though.

But to get back to the food…Jimmie and Maria Thereza were regulars at the Fisch Restaurant when they lived in Berlin. This secret little gem of a place was opened by a former World Cup soccer star who played for Turkey, and the walls show photos of his soccer days, while hundreds of cards from fans of his fish hang from the ceiling. The menu features photographs of the different fish you can order, most of them sharing camera time with a tall can of beer, not to make a beverage suggestion, but to help indicate the size of the fish. I had a plate full of the tasty little red ones.

But to get back to the food…Jimmie and Maria Thereza were regulars at the Fisch Restaurant when they lived in Berlin. This secret little gem of a place was opened by a former World Cup soccer star who played for Turkey, and the walls show photos of his soccer days, while hundreds of cards from fans of his fish hang from the ceiling. The menu features photographs of the different fish you can order, most of them sharing camera time with a tall can of beer, not to make a beverage suggestion, but to help indicate the size of the fish. I had a plate full of the tasty little red ones.

In the later hours, strong coffee and friendly shots of anise liquor circulated, as a couple of tables of smartly dressed Turkish men talked seriously over swirling tendrils of shisha that danced in the low yellow light, disappearing like the hours before my plane ride home.