Art

Entering the Temporary Art Zone with Hakim Bey

Entering the Temporary Art Zone with Hakim Bey

by Ayesha Adamo

“The art, such as it is, comes into existence only in the moment of its own disappearance; afterwards it will be invisible—except to the spirits” – Peter Lamborn Wilson

• • •

by Ayesha Adamo

“The art, such as it is, comes into existence only in the moment of its own disappearance; afterwards it will be invisible—except to the spirits” – Peter Lamborn Wilson

• • •

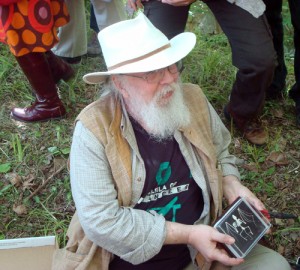

On May 15th 2010, Peter Lamborn Wilson, known to many as Hakim Bey, completed another happening in a series of events aimed at re-enchanting the landscape of forgotten or not-yet-revealed sacred places in upstate New York. These acts of “Endarkenment,” a term Peter uses to mean “fear & respect as well as love for Nature,” are the culmination of his last ten years of research in Ulster County and the surrounding areas. He’s putting the magick he dug up back into the land.

Peter has called this a “temporary landscape installation piece.” It is art that disappears and defies a fetishized place on the

On May 15th 2010, Peter Lamborn Wilson, known to many as Hakim Bey, completed another happening in a series of events aimed at re-enchanting the landscape of forgotten or not-yet-revealed sacred places in upstate New York. These acts of “Endarkenment,” a term Peter uses to mean “fear & respect as well as love for Nature,” are the culmination of his last ten years of research in Ulster County and the surrounding areas. He’s putting the magick he dug up back into the land.

Peter has called this a “temporary landscape installation piece.” It is art that disappears and defies a fetishized place on the  gallery wall. While it bears a resemblance to landscape art, it is more than that, for its goal is to enact the magick of enchantment on the land where each work is performed. The documentation of each of these works includes a hand-written essay, and this May 15th working also featured a large storyboard with pictures and photographs significant to the occasion.

After Peter’s short talk about his research leading up to this event, a few helpers went ahead to make preparations, followed by Peter and his large box labeled “Jukes.” Slowly, the rest of us followed in single file along the narrow towpath where mules used to tread, hauling boats, when the Delaware and Hudson Canal was operational.

gallery wall. While it bears a resemblance to landscape art, it is more than that, for its goal is to enact the magick of enchantment on the land where each work is performed. The documentation of each of these works includes a hand-written essay, and this May 15th working also featured a large storyboard with pictures and photographs significant to the occasion.

After Peter’s short talk about his research leading up to this event, a few helpers went ahead to make preparations, followed by Peter and his large box labeled “Jukes.” Slowly, the rest of us followed in single file along the narrow towpath where mules used to tread, hauling boats, when the Delaware and Hudson Canal was operational.

In my understanding of it, there were three main groups called forth for reawakening in this work:

one group that has already disappeared, one that is disappearing, and one that now returns.

The group that has already disappeared is known as the Jukes, or at least that’s the name that flawed social scientists gave to this now infamous community of families when they were the target of eugenics studies in the 1800’s. The flaws in these studies have since been recognized, but what still remains fascinating about the Jukes is the reason that they were targeted for such studies to begin with: they were what Peter calls, “a drop-out society,” not unlike the modern day Ramapough Mountain Indians from New Jersey, who were the subject of the recent New Yorker article “Strangers on the Mountain.” But the Ramapough Mountain Indians,

In my understanding of it, there were three main groups called forth for reawakening in this work:

one group that has already disappeared, one that is disappearing, and one that now returns.

The group that has already disappeared is known as the Jukes, or at least that’s the name that flawed social scientists gave to this now infamous community of families when they were the target of eugenics studies in the 1800’s. The flaws in these studies have since been recognized, but what still remains fascinating about the Jukes is the reason that they were targeted for such studies to begin with: they were what Peter calls, “a drop-out society,” not unlike the modern day Ramapough Mountain Indians from New Jersey, who were the subject of the recent New Yorker article “Strangers on the Mountain.” But the Ramapough Mountain Indians,  or “Jackson Whites,” as they have been called, have kept their society, even with the skyscrapers of New York threatening on the horizon. They have also kept their mountain - even with the enduring effects of the toxic waste that the old Ford factory dumped on it decades before. The Jukes have not been so lucky – if you can call it luck. While descendants of the Jukes surely still exist, their isolated drop-out community has vanished, and they seem a distant legend in the Ulster County of 2010. All that remains of the Jukes today can be found in a poorhouse graveyard in New Paltz that was re-discovered in 2001, and in the records kept by the poorhouse and those in the archives of the SUNY Albany library. The once vibrant living community of Jukes has now vanished.

or “Jackson Whites,” as they have been called, have kept their society, even with the skyscrapers of New York threatening on the horizon. They have also kept their mountain - even with the enduring effects of the toxic waste that the old Ford factory dumped on it decades before. The Jukes have not been so lucky – if you can call it luck. While descendants of the Jukes surely still exist, their isolated drop-out community has vanished, and they seem a distant legend in the Ulster County of 2010. All that remains of the Jukes today can be found in a poorhouse graveyard in New Paltz that was re-discovered in 2001, and in the records kept by the poorhouse and those in the archives of the SUNY Albany library. The once vibrant living community of Jukes has now vanished.

The second group, the group that is in the process of vanishing, is the bat community. All along the East Coast and into the Midwest, bats have been found dead in the hundreds of thousands.

The second group, the group that is in the process of vanishing, is the bat community. All along the East Coast and into the Midwest, bats have been found dead in the hundreds of thousands.  The bats are dying of “white-nose syndrome,” so named for the white fungus, Geomyces destructans, that can be seen on the muzzles of infected bats. It is still uncertain whether the fungus is the disease or whether it is able to take hold of an immune system already weakened by some other disease, though it seems that the fungus itself is the culprit. Bats are a major predator to insects, not just the insects that interfere with us on a hot summer day, but also those that interfere with the growth of crops. The threat of imbalance in the ecosystem, as well as the possibility of extinction for many species of bats, is a serious concern for us all as we watch this community of animals suddenly disappear.

The bats are dying of “white-nose syndrome,” so named for the white fungus, Geomyces destructans, that can be seen on the muzzles of infected bats. It is still uncertain whether the fungus is the disease or whether it is able to take hold of an immune system already weakened by some other disease, though it seems that the fungus itself is the culprit. Bats are a major predator to insects, not just the insects that interfere with us on a hot summer day, but also those that interfere with the growth of crops. The threat of imbalance in the ecosystem, as well as the possibility of extinction for many species of bats, is a serious concern for us all as we watch this community of animals suddenly disappear.  The last group, the one that returns, is the cement itself, which was to be the bonding agent of all that went into this day’s working of Endarkenment. Standing on the aqueduct bridge abutment designed by Roebling in 1850 and overlooking the Rondout Creek, it seemed only fitting that the cement used for this occasion should be Rosendale Natural Cement, which was the business that founded the nearby town of Rosendale during the construction of the Delaware and Hudson Canal. The cement was first discovered in Rosendale during the excavation of the canal bed for the D & H Canal in 1825, and would later be used as one of the materials in the building of the canal itself. Rosendale Natural Cement was also used in the construction of Roebling’s aqueduct bridge, the remaining abutment on which we then stood, and in his later and more famous project, the Brooklyn Bridge. Despite the popularity of Rosendale Cement in the nineteenth century, the introduction of faster-setting Portland Cement meant the end of natural cement production in the twentieth century. By 1970, the last of the cement mines in Rosendale were closed. Natural cement was no longer available.

But in 2004, natural cement made a surprising return when Edison Coatings, Inc decided to resurrect production of Rosendale Natural Cement. The main reason behind this comeback was the need to restore buildings and monuments that were originally constructed using natural cement,

The last group, the one that returns, is the cement itself, which was to be the bonding agent of all that went into this day’s working of Endarkenment. Standing on the aqueduct bridge abutment designed by Roebling in 1850 and overlooking the Rondout Creek, it seemed only fitting that the cement used for this occasion should be Rosendale Natural Cement, which was the business that founded the nearby town of Rosendale during the construction of the Delaware and Hudson Canal. The cement was first discovered in Rosendale during the excavation of the canal bed for the D & H Canal in 1825, and would later be used as one of the materials in the building of the canal itself. Rosendale Natural Cement was also used in the construction of Roebling’s aqueduct bridge, the remaining abutment on which we then stood, and in his later and more famous project, the Brooklyn Bridge. Despite the popularity of Rosendale Cement in the nineteenth century, the introduction of faster-setting Portland Cement meant the end of natural cement production in the twentieth century. By 1970, the last of the cement mines in Rosendale were closed. Natural cement was no longer available.

But in 2004, natural cement made a surprising return when Edison Coatings, Inc decided to resurrect production of Rosendale Natural Cement. The main reason behind this comeback was the need to restore buildings and monuments that were originally constructed using natural cement,  though it turns out that Rosendale Natural Cement is actually “greener” than modern Portland Cement. Due to its much lower firing temperatures and the ease of grinding, natural cement requires less energy to produce.

As we gathered around Peter to watch this artwork in its vanishing, an artwork that is being done for those who vanish, the scent of copal mixed with other incenses - those he had burning on the rock before us, and those of the forest itself.

though it turns out that Rosendale Natural Cement is actually “greener” than modern Portland Cement. Due to its much lower firing temperatures and the ease of grinding, natural cement requires less energy to produce.

As we gathered around Peter to watch this artwork in its vanishing, an artwork that is being done for those who vanish, the scent of copal mixed with other incenses - those he had burning on the rock before us, and those of the forest itself.

The artwork happened simply. There was little ceremony, perhaps to the confusion of some in attendance who had hoped for a chant or a reading. Peter presented items, one by one, and placed them into a hole in the ground that would be filled with cement. Among these were crystals, a fancy bat skeleton from Carolina Biological, the remains of the incense itself…it made me wonder: must things be buried that they may return? Do we re-enchant our environment when we return to the point zero?

For Peter’s magickal purposes in this act of art, I believe it was significant that the natural cement local to this area, the one element in the work that had gone from a state of disappearance into new life, should be the bonding agent for all the others. As the creation of this temporary installation piece was executed, we watched closely as items disappeared into the hole, as their physical passage from the box labeled “Jukes” into the hole before us disappeared into memory. All of this was then sealed by cement and rocks found around the site the day before. While the process of art may have vanished, the evidence of the act endures. Like the Brooklyn Bridge, the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, and Grand Central Terminal, this momentary work was made using Rosendale Natural Cement. Its purpose is beyond that of a monument, but the place of Endarkenment was built to last just the same, even if it was now only visible to the spirits, as Peter says.

The artwork happened simply. There was little ceremony, perhaps to the confusion of some in attendance who had hoped for a chant or a reading. Peter presented items, one by one, and placed them into a hole in the ground that would be filled with cement. Among these were crystals, a fancy bat skeleton from Carolina Biological, the remains of the incense itself…it made me wonder: must things be buried that they may return? Do we re-enchant our environment when we return to the point zero?

For Peter’s magickal purposes in this act of art, I believe it was significant that the natural cement local to this area, the one element in the work that had gone from a state of disappearance into new life, should be the bonding agent for all the others. As the creation of this temporary installation piece was executed, we watched closely as items disappeared into the hole, as their physical passage from the box labeled “Jukes” into the hole before us disappeared into memory. All of this was then sealed by cement and rocks found around the site the day before. While the process of art may have vanished, the evidence of the act endures. Like the Brooklyn Bridge, the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, and Grand Central Terminal, this momentary work was made using Rosendale Natural Cement. Its purpose is beyond that of a monument, but the place of Endarkenment was built to last just the same, even if it was now only visible to the spirits, as Peter says.

After we traveled back along the narrow towpath and out of the woods, a little boy who was playing pointed up to the sky, and we all saw it: a small rainbow showing itself faintly through the trees, though it hadn’t rained at all. The enchantment was complete, and the signs of this were not only visible to the spirits, but also to us.

*** Peter's statements that have been quoted here are from the press release of a previous related event. You can read his writing on that event here:

http://www.sevenpillarshouse.org/article/first_vanishing_art/

After we traveled back along the narrow towpath and out of the woods, a little boy who was playing pointed up to the sky, and we all saw it: a small rainbow showing itself faintly through the trees, though it hadn’t rained at all. The enchantment was complete, and the signs of this were not only visible to the spirits, but also to us.

*** Peter's statements that have been quoted here are from the press release of a previous related event. You can read his writing on that event here:

http://www.sevenpillarshouse.org/article/first_vanishing_art/

7VPZM2AUKGJM

7VPZM2AUKGJM

Spargel, Fish, and Farewells

Spargel, Fish, and Farewells

by Ayesha Adamo

It seemed that the moment my plane landed in Berlin, Spargel season had officially begun. There was hardly a restaurant in the city that wasn’t offering some sort of Spargel-special, four courses of Spargel…even dessert. I had

It seemed that the moment my plane landed in Berlin, Spargel season had officially begun. There was hardly a restaurant in the city that wasn’t offering some sort of Spargel-special, four courses of Spargel…even dessert. I had  never heard of Spargel before, but I learned pretty quick. Spargel is this thick white asparagus that Germans seem to go crazy for, especially because it’s only available for two weeks out of the entire year. It’s a little bit phallic looking, and maybe that’s part of the charm, too. You can see piles of it here, in this photo I took at the Turkish market in Kotti:

never heard of Spargel before, but I learned pretty quick. Spargel is this thick white asparagus that Germans seem to go crazy for, especially because it’s only available for two weeks out of the entire year. It’s a little bit phallic looking, and maybe that’s part of the charm, too. You can see piles of it here, in this photo I took at the Turkish market in Kotti:  The fantastic deli, “Rogacki,” where I got my first taste of Berlin, was no exception to the rule of Spargel either.

Rogacki is the deli to end all delis. I mean, I used to deeply mourn the loss of Second Avenue Deli down in the East Village after it lost the rent war to a Chase Bank branch (which I suppose is exactly what all those yuppies that have taken over the neighborhood deserve anyway), but Rogacki is in a whole other class.

The fantastic deli, “Rogacki,” where I got my first taste of Berlin, was no exception to the rule of Spargel either.

Rogacki is the deli to end all delis. I mean, I used to deeply mourn the loss of Second Avenue Deli down in the East Village after it lost the rent war to a Chase Bank branch (which I suppose is exactly what all those yuppies that have taken over the neighborhood deserve anyway), but Rogacki is in a whole other class.  Rogacki is in Charlottenburg on Wilmersdorfer Strasse, just half a block from the Bismarckstrasse U-bahn. Everyone stands at the counter to eat, though there were a few

Rogacki is in Charlottenburg on Wilmersdorfer Strasse, just half a block from the Bismarckstrasse U-bahn. Everyone stands at the counter to eat, though there were a few  tables out front in recognition of the spring weather.

In addition to the seemingly endless window cases of beautiful sausages and deli meats, this place has some serious fish

tables out front in recognition of the spring weather.

In addition to the seemingly endless window cases of beautiful sausages and deli meats, this place has some serious fish  (the big guy with the sad look on his face at the top of this article is also a Rogacki resident). We ate the most amazing fish soup and grilled fish with vegetables, all prepared by the no-nonsense ladies at the counter before our eyes. In keeping with the reputation

(the big guy with the sad look on his face at the top of this article is also a Rogacki resident). We ate the most amazing fish soup and grilled fish with vegetables, all prepared by the no-nonsense ladies at the counter before our eyes. In keeping with the reputation  of this family-run business that started in 1928 selling fish exclusively, they still smoke their own fish and eel on site here. But nowadays, there’s also fresh turkey,

of this family-run business that started in 1928 selling fish exclusively, they still smoke their own fish and eel on site here. But nowadays, there’s also fresh turkey,  venison, duck and on and on…

http://rogacki.de/ro/roga.htm

In general, Berlin is a great place for fish and seafood, and my last night’s dinner at the amazing Turkish-run Fisch Restaurant was the perfect bookend to my Rogacki experience.

Balikci Ergün is on Lüneburger Strasse under the S-Bahn, across the Spree and not so far from Bellevue Station. You will know it by the blue and yellow sign saying “Fisch Restaurant.”

venison, duck and on and on…

http://rogacki.de/ro/roga.htm

In general, Berlin is a great place for fish and seafood, and my last night’s dinner at the amazing Turkish-run Fisch Restaurant was the perfect bookend to my Rogacki experience.

Balikci Ergün is on Lüneburger Strasse under the S-Bahn, across the Spree and not so far from Bellevue Station. You will know it by the blue and yellow sign saying “Fisch Restaurant.”

I’m pretty sure that the entrance on Lüneburger Strasse is a back entrance devoted to their fish distribution business, but after a few moments of confusion and seeing what was behind door number one, two and three, I eventually found my way into the restaurant.

This last night was a night to say goodbye to Berlin, and to Maria Thereza Alves and Jimmie Durham, whose three exhibits during gallery weekend and talk at the House for World Culture with Mick Taussig were an important part of my visit.

The conversation at our table twisted and turned into and out of politics and Art, Europe and the Americas. For the struggling and flailing artist that I am, it was fascinating to hear about how someone with a career as enduring as Jimmie’s would repeatedly turn down the opportunity to have a PBS documentary done on his life and work, responding that this sort of documentary kills the artwork, and the artist who made it, every time. I guess it’s the reaction I would expect from the man who’s just displayed a gallery of modern-art-stuffed-mooseheads (like what you'd see in a fancy hunting lodge, except this was Art - not taxidermy). It's hopeful to see someone cleverly poking fun at the bourgeois trophies that great works of Art have become – or always were, perhaps. But for a young creative who’s tired of trying to reinvent her Art’s PR campaign on a weekly basis, and who enters a state of nearly-epileptic joy anytime some stranger deigns to add a thumbs-up “like” to her latest facebook post, the idea of turning down a documentary makes the eyes a little moist…a little moist. I get it, though.

I’m pretty sure that the entrance on Lüneburger Strasse is a back entrance devoted to their fish distribution business, but after a few moments of confusion and seeing what was behind door number one, two and three, I eventually found my way into the restaurant.

This last night was a night to say goodbye to Berlin, and to Maria Thereza Alves and Jimmie Durham, whose three exhibits during gallery weekend and talk at the House for World Culture with Mick Taussig were an important part of my visit.

The conversation at our table twisted and turned into and out of politics and Art, Europe and the Americas. For the struggling and flailing artist that I am, it was fascinating to hear about how someone with a career as enduring as Jimmie’s would repeatedly turn down the opportunity to have a PBS documentary done on his life and work, responding that this sort of documentary kills the artwork, and the artist who made it, every time. I guess it’s the reaction I would expect from the man who’s just displayed a gallery of modern-art-stuffed-mooseheads (like what you'd see in a fancy hunting lodge, except this was Art - not taxidermy). It's hopeful to see someone cleverly poking fun at the bourgeois trophies that great works of Art have become – or always were, perhaps. But for a young creative who’s tired of trying to reinvent her Art’s PR campaign on a weekly basis, and who enters a state of nearly-epileptic joy anytime some stranger deigns to add a thumbs-up “like” to her latest facebook post, the idea of turning down a documentary makes the eyes a little moist…a little moist. I get it, though.

But to get back to the food...Jimmie and Maria Thereza were regulars at the Fisch Restaurant when they lived in Berlin. This secret little gem of a place was opened by a former World Cup soccer star who played for Turkey, and the walls show photos of his soccer days, while hundreds of cards from fans of his fish hang from the ceiling. The menu features photographs of the different fish you can order, most of them sharing camera time with a tall can of beer, not to make a beverage suggestion, but to help indicate the size of the fish. I had a plate full of the tasty little red ones.

In the later hours, strong coffee and friendly shots of anise liquor circulated, as a couple of tables of smartly dressed Turkish men talked seriously over swirling tendrils of shisha that danced in the low yellow light, disappearing like the hours before my plane ride home.

But to get back to the food...Jimmie and Maria Thereza were regulars at the Fisch Restaurant when they lived in Berlin. This secret little gem of a place was opened by a former World Cup soccer star who played for Turkey, and the walls show photos of his soccer days, while hundreds of cards from fans of his fish hang from the ceiling. The menu features photographs of the different fish you can order, most of them sharing camera time with a tall can of beer, not to make a beverage suggestion, but to help indicate the size of the fish. I had a plate full of the tasty little red ones.

In the later hours, strong coffee and friendly shots of anise liquor circulated, as a couple of tables of smartly dressed Turkish men talked seriously over swirling tendrils of shisha that danced in the low yellow light, disappearing like the hours before my plane ride home.

It seemed that the moment my plane landed in Berlin, Spargel season had officially begun. There was hardly a restaurant in the city that wasn’t offering some sort of Spargel-special, four courses of Spargel…even dessert. I had

It seemed that the moment my plane landed in Berlin, Spargel season had officially begun. There was hardly a restaurant in the city that wasn’t offering some sort of Spargel-special, four courses of Spargel…even dessert. I had  never heard of Spargel before, but I learned pretty quick. Spargel is this thick white asparagus that Germans seem to go crazy for, especially because it’s only available for two weeks out of the entire year. It’s a little bit phallic looking, and maybe that’s part of the charm, too. You can see piles of it here, in this photo I took at the Turkish market in Kotti:

never heard of Spargel before, but I learned pretty quick. Spargel is this thick white asparagus that Germans seem to go crazy for, especially because it’s only available for two weeks out of the entire year. It’s a little bit phallic looking, and maybe that’s part of the charm, too. You can see piles of it here, in this photo I took at the Turkish market in Kotti:  The fantastic deli, “Rogacki,” where I got my first taste of Berlin, was no exception to the rule of Spargel either.

Rogacki is the deli to end all delis. I mean, I used to deeply mourn the loss of Second Avenue Deli down in the East Village after it lost the rent war to a Chase Bank branch (which I suppose is exactly what all those yuppies that have taken over the neighborhood deserve anyway), but Rogacki is in a whole other class.

The fantastic deli, “Rogacki,” where I got my first taste of Berlin, was no exception to the rule of Spargel either.

Rogacki is the deli to end all delis. I mean, I used to deeply mourn the loss of Second Avenue Deli down in the East Village after it lost the rent war to a Chase Bank branch (which I suppose is exactly what all those yuppies that have taken over the neighborhood deserve anyway), but Rogacki is in a whole other class.  Rogacki is in Charlottenburg on Wilmersdorfer Strasse, just half a block from the Bismarckstrasse U-bahn. Everyone stands at the counter to eat, though there were a few

Rogacki is in Charlottenburg on Wilmersdorfer Strasse, just half a block from the Bismarckstrasse U-bahn. Everyone stands at the counter to eat, though there were a few  tables out front in recognition of the spring weather.

In addition to the seemingly endless window cases of beautiful sausages and deli meats, this place has some serious fish

tables out front in recognition of the spring weather.

In addition to the seemingly endless window cases of beautiful sausages and deli meats, this place has some serious fish  (the big guy with the sad look on his face at the top of this article is also a Rogacki resident). We ate the most amazing fish soup and grilled fish with vegetables, all prepared by the no-nonsense ladies at the counter before our eyes. In keeping with the reputation

(the big guy with the sad look on his face at the top of this article is also a Rogacki resident). We ate the most amazing fish soup and grilled fish with vegetables, all prepared by the no-nonsense ladies at the counter before our eyes. In keeping with the reputation  of this family-run business that started in 1928 selling fish exclusively, they still smoke their own fish and eel on site here. But nowadays, there’s also fresh turkey,

of this family-run business that started in 1928 selling fish exclusively, they still smoke their own fish and eel on site here. But nowadays, there’s also fresh turkey,  venison, duck and on and on…

http://rogacki.de/ro/roga.htm

In general, Berlin is a great place for fish and seafood, and my last night’s dinner at the amazing Turkish-run Fisch Restaurant was the perfect bookend to my Rogacki experience.

Balikci Ergün is on Lüneburger Strasse under the S-Bahn, across the Spree and not so far from Bellevue Station. You will know it by the blue and yellow sign saying “Fisch Restaurant.”

venison, duck and on and on…

http://rogacki.de/ro/roga.htm

In general, Berlin is a great place for fish and seafood, and my last night’s dinner at the amazing Turkish-run Fisch Restaurant was the perfect bookend to my Rogacki experience.

Balikci Ergün is on Lüneburger Strasse under the S-Bahn, across the Spree and not so far from Bellevue Station. You will know it by the blue and yellow sign saying “Fisch Restaurant.”

I’m pretty sure that the entrance on Lüneburger Strasse is a back entrance devoted to their fish distribution business, but after a few moments of confusion and seeing what was behind door number one, two and three, I eventually found my way into the restaurant.

This last night was a night to say goodbye to Berlin, and to Maria Thereza Alves and Jimmie Durham, whose three exhibits during gallery weekend and talk at the House for World Culture with Mick Taussig were an important part of my visit.

The conversation at our table twisted and turned into and out of politics and Art, Europe and the Americas. For the struggling and flailing artist that I am, it was fascinating to hear about how someone with a career as enduring as Jimmie’s would repeatedly turn down the opportunity to have a PBS documentary done on his life and work, responding that this sort of documentary kills the artwork, and the artist who made it, every time. I guess it’s the reaction I would expect from the man who’s just displayed a gallery of modern-art-stuffed-mooseheads (like what you'd see in a fancy hunting lodge, except this was Art - not taxidermy). It's hopeful to see someone cleverly poking fun at the bourgeois trophies that great works of Art have become – or always were, perhaps. But for a young creative who’s tired of trying to reinvent her Art’s PR campaign on a weekly basis, and who enters a state of nearly-epileptic joy anytime some stranger deigns to add a thumbs-up “like” to her latest facebook post, the idea of turning down a documentary makes the eyes a little moist…a little moist. I get it, though.

I’m pretty sure that the entrance on Lüneburger Strasse is a back entrance devoted to their fish distribution business, but after a few moments of confusion and seeing what was behind door number one, two and three, I eventually found my way into the restaurant.

This last night was a night to say goodbye to Berlin, and to Maria Thereza Alves and Jimmie Durham, whose three exhibits during gallery weekend and talk at the House for World Culture with Mick Taussig were an important part of my visit.

The conversation at our table twisted and turned into and out of politics and Art, Europe and the Americas. For the struggling and flailing artist that I am, it was fascinating to hear about how someone with a career as enduring as Jimmie’s would repeatedly turn down the opportunity to have a PBS documentary done on his life and work, responding that this sort of documentary kills the artwork, and the artist who made it, every time. I guess it’s the reaction I would expect from the man who’s just displayed a gallery of modern-art-stuffed-mooseheads (like what you'd see in a fancy hunting lodge, except this was Art - not taxidermy). It's hopeful to see someone cleverly poking fun at the bourgeois trophies that great works of Art have become – or always were, perhaps. But for a young creative who’s tired of trying to reinvent her Art’s PR campaign on a weekly basis, and who enters a state of nearly-epileptic joy anytime some stranger deigns to add a thumbs-up “like” to her latest facebook post, the idea of turning down a documentary makes the eyes a little moist…a little moist. I get it, though.

But to get back to the food...Jimmie and Maria Thereza were regulars at the Fisch Restaurant when they lived in Berlin. This secret little gem of a place was opened by a former World Cup soccer star who played for Turkey, and the walls show photos of his soccer days, while hundreds of cards from fans of his fish hang from the ceiling. The menu features photographs of the different fish you can order, most of them sharing camera time with a tall can of beer, not to make a beverage suggestion, but to help indicate the size of the fish. I had a plate full of the tasty little red ones.

In the later hours, strong coffee and friendly shots of anise liquor circulated, as a couple of tables of smartly dressed Turkish men talked seriously over swirling tendrils of shisha that danced in the low yellow light, disappearing like the hours before my plane ride home.

But to get back to the food...Jimmie and Maria Thereza were regulars at the Fisch Restaurant when they lived in Berlin. This secret little gem of a place was opened by a former World Cup soccer star who played for Turkey, and the walls show photos of his soccer days, while hundreds of cards from fans of his fish hang from the ceiling. The menu features photographs of the different fish you can order, most of them sharing camera time with a tall can of beer, not to make a beverage suggestion, but to help indicate the size of the fish. I had a plate full of the tasty little red ones.

In the later hours, strong coffee and friendly shots of anise liquor circulated, as a couple of tables of smartly dressed Turkish men talked seriously over swirling tendrils of shisha that danced in the low yellow light, disappearing like the hours before my plane ride home.

Memorials: Berlin

Memorials: Berlin

by Ayesha Adamo

While in Berlin, I visited two large-scale Holocaust memorials – one was the well-publicized and controversial Holocaust Memorial near the Brandenburg Gate; the other was Gleis 17, a seemingly less known spot at Grünewald Station on the S-Bahn.

The official title of the first memorial is Denkmal für die emordeten Juden Europas, or Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, but no one seems to want to use this title. Most just call it Holocaust Memorial and everyone appears to know which one you mean, which is amazing when you consider that every turn of a street corner in Berlin brings a different plaque or statue to be discovered. Whether it be names and dates in brass on the ground, bullet dents building character on a beautiful facade, or the graffiti that’s left up for posterity, every manmade surface in Berlin carries the marks of who-wuz-here and what happened before, one great layer of impasto after another.

The Holocaust Memorial doesn’t have graffiti, though, which has been cause for much controversy – not because people feel that it would be better with graffiti, but because Degussa, the company that made the graffiti-proof coating for the large stone slabs that populate this monument, also made Zyklon B during WWII.

While the inclusion of the word “Murdered” in the Memorial’s full title has the sound of something flashy, the actual monument is stoic and austere. Each of the rectangular stones is of a different height, and the ground that the stones stand on has visible waves of hills and valleys, creating a kind of visual discord that, like the event the

While in Berlin, I visited two large-scale Holocaust memorials – one was the well-publicized and controversial Holocaust Memorial near the Brandenburg Gate; the other was Gleis 17, a seemingly less known spot at Grünewald Station on the S-Bahn.

The official title of the first memorial is Denkmal für die emordeten Juden Europas, or Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, but no one seems to want to use this title. Most just call it Holocaust Memorial and everyone appears to know which one you mean, which is amazing when you consider that every turn of a street corner in Berlin brings a different plaque or statue to be discovered. Whether it be names and dates in brass on the ground, bullet dents building character on a beautiful facade, or the graffiti that’s left up for posterity, every manmade surface in Berlin carries the marks of who-wuz-here and what happened before, one great layer of impasto after another.

The Holocaust Memorial doesn’t have graffiti, though, which has been cause for much controversy – not because people feel that it would be better with graffiti, but because Degussa, the company that made the graffiti-proof coating for the large stone slabs that populate this monument, also made Zyklon B during WWII.

While the inclusion of the word “Murdered” in the Memorial’s full title has the sound of something flashy, the actual monument is stoic and austere. Each of the rectangular stones is of a different height, and the ground that the stones stand on has visible waves of hills and valleys, creating a kind of visual discord that, like the event the  monument recognizes, is difficult to comprehend in any simple kind of understanding. The vertical parallels of stones, and the grey grids created between them, give the feeling of some fleeting yet absolute form and structure, like entering deeper and deeper into the labyrinth of infinity.

The Memorial expects you to be a part of it, to be in it. I watched a group of kids playing games and leaping from stone to stone, a high-stakes version of hopscotch. They were reclaiming the tall grey pillars as their playground in a way that seemed obvious and natural. And why wouldn’t this be a place for play as much as anything else? There are no signs here to state otherwise.

monument recognizes, is difficult to comprehend in any simple kind of understanding. The vertical parallels of stones, and the grey grids created between them, give the feeling of some fleeting yet absolute form and structure, like entering deeper and deeper into the labyrinth of infinity.

The Memorial expects you to be a part of it, to be in it. I watched a group of kids playing games and leaping from stone to stone, a high-stakes version of hopscotch. They were reclaiming the tall grey pillars as their playground in a way that seemed obvious and natural. And why wouldn’t this be a place for play as much as anything else? There are no signs here to state otherwise.

Gleis 17 was the site of deportations to extermination camps during WWII. The tracks are no longer in use, but remain as part of this memorial, bending off ominously in the distance. Each of the iron grates along the length of the platform is engraved with the date, destination, and number of Jewish passengers on a different deportation.

The tracks here are now quiet and serene. There was hardly anyone else around when I visited, but a fresh single rose left at one of the grates proved that others had been there recently. The only marks of the many that stood there decades before were the numbers pressed into iron every few feet, but there was a feeling about standing there that marked the place unmistakably.

Gleis 17 was the site of deportations to extermination camps during WWII. The tracks are no longer in use, but remain as part of this memorial, bending off ominously in the distance. Each of the iron grates along the length of the platform is engraved with the date, destination, and number of Jewish passengers on a different deportation.

The tracks here are now quiet and serene. There was hardly anyone else around when I visited, but a fresh single rose left at one of the grates proved that others had been there recently. The only marks of the many that stood there decades before were the numbers pressed into iron every few feet, but there was a feeling about standing there that marked the place unmistakably. A little dandelion pushing through the platform grate caught my eye, and at one end of the station trees have grown up through parts of the tracks. Here, nature is reclaiming both the tracks and the memorial. New life is filling up all the spaces between grates and between tracks, but when we left on the S-Bahn, there was a Roma playing accordion while his son held a cup out that no one was filling up. Hardly anyone even looked up.

A little dandelion pushing through the platform grate caught my eye, and at one end of the station trees have grown up through parts of the tracks. Here, nature is reclaiming both the tracks and the memorial. New life is filling up all the spaces between grates and between tracks, but when we left on the S-Bahn, there was a Roma playing accordion while his son held a cup out that no one was filling up. Hardly anyone even looked up.

While in Berlin, I visited two large-scale Holocaust memorials – one was the well-publicized and controversial Holocaust Memorial near the Brandenburg Gate; the other was Gleis 17, a seemingly less known spot at Grünewald Station on the S-Bahn.

The official title of the first memorial is Denkmal für die emordeten Juden Europas, or Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, but no one seems to want to use this title. Most just call it Holocaust Memorial and everyone appears to know which one you mean, which is amazing when you consider that every turn of a street corner in Berlin brings a different plaque or statue to be discovered. Whether it be names and dates in brass on the ground, bullet dents building character on a beautiful facade, or the graffiti that’s left up for posterity, every manmade surface in Berlin carries the marks of who-wuz-here and what happened before, one great layer of impasto after another.

The Holocaust Memorial doesn’t have graffiti, though, which has been cause for much controversy – not because people feel that it would be better with graffiti, but because Degussa, the company that made the graffiti-proof coating for the large stone slabs that populate this monument, also made Zyklon B during WWII.

While the inclusion of the word “Murdered” in the Memorial’s full title has the sound of something flashy, the actual monument is stoic and austere. Each of the rectangular stones is of a different height, and the ground that the stones stand on has visible waves of hills and valleys, creating a kind of visual discord that, like the event the

While in Berlin, I visited two large-scale Holocaust memorials – one was the well-publicized and controversial Holocaust Memorial near the Brandenburg Gate; the other was Gleis 17, a seemingly less known spot at Grünewald Station on the S-Bahn.

The official title of the first memorial is Denkmal für die emordeten Juden Europas, or Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, but no one seems to want to use this title. Most just call it Holocaust Memorial and everyone appears to know which one you mean, which is amazing when you consider that every turn of a street corner in Berlin brings a different plaque or statue to be discovered. Whether it be names and dates in brass on the ground, bullet dents building character on a beautiful facade, or the graffiti that’s left up for posterity, every manmade surface in Berlin carries the marks of who-wuz-here and what happened before, one great layer of impasto after another.

The Holocaust Memorial doesn’t have graffiti, though, which has been cause for much controversy – not because people feel that it would be better with graffiti, but because Degussa, the company that made the graffiti-proof coating for the large stone slabs that populate this monument, also made Zyklon B during WWII.

While the inclusion of the word “Murdered” in the Memorial’s full title has the sound of something flashy, the actual monument is stoic and austere. Each of the rectangular stones is of a different height, and the ground that the stones stand on has visible waves of hills and valleys, creating a kind of visual discord that, like the event the  monument recognizes, is difficult to comprehend in any simple kind of understanding. The vertical parallels of stones, and the grey grids created between them, give the feeling of some fleeting yet absolute form and structure, like entering deeper and deeper into the labyrinth of infinity.

The Memorial expects you to be a part of it, to be in it. I watched a group of kids playing games and leaping from stone to stone, a high-stakes version of hopscotch. They were reclaiming the tall grey pillars as their playground in a way that seemed obvious and natural. And why wouldn’t this be a place for play as much as anything else? There are no signs here to state otherwise.

monument recognizes, is difficult to comprehend in any simple kind of understanding. The vertical parallels of stones, and the grey grids created between them, give the feeling of some fleeting yet absolute form and structure, like entering deeper and deeper into the labyrinth of infinity.

The Memorial expects you to be a part of it, to be in it. I watched a group of kids playing games and leaping from stone to stone, a high-stakes version of hopscotch. They were reclaiming the tall grey pillars as their playground in a way that seemed obvious and natural. And why wouldn’t this be a place for play as much as anything else? There are no signs here to state otherwise.

Gleis 17 was the site of deportations to extermination camps during WWII. The tracks are no longer in use, but remain as part of this memorial, bending off ominously in the distance. Each of the iron grates along the length of the platform is engraved with the date, destination, and number of Jewish passengers on a different deportation.

The tracks here are now quiet and serene. There was hardly anyone else around when I visited, but a fresh single rose left at one of the grates proved that others had been there recently. The only marks of the many that stood there decades before were the numbers pressed into iron every few feet, but there was a feeling about standing there that marked the place unmistakably.

Gleis 17 was the site of deportations to extermination camps during WWII. The tracks are no longer in use, but remain as part of this memorial, bending off ominously in the distance. Each of the iron grates along the length of the platform is engraved with the date, destination, and number of Jewish passengers on a different deportation.

The tracks here are now quiet and serene. There was hardly anyone else around when I visited, but a fresh single rose left at one of the grates proved that others had been there recently. The only marks of the many that stood there decades before were the numbers pressed into iron every few feet, but there was a feeling about standing there that marked the place unmistakably. A little dandelion pushing through the platform grate caught my eye, and at one end of the station trees have grown up through parts of the tracks. Here, nature is reclaiming both the tracks and the memorial. New life is filling up all the spaces between grates and between tracks, but when we left on the S-Bahn, there was a Roma playing accordion while his son held a cup out that no one was filling up. Hardly anyone even looked up.

A little dandelion pushing through the platform grate caught my eye, and at one end of the station trees have grown up through parts of the tracks. Here, nature is reclaiming both the tracks and the memorial. New life is filling up all the spaces between grates and between tracks, but when we left on the S-Bahn, there was a Roma playing accordion while his son held a cup out that no one was filling up. Hardly anyone even looked up.